By Scott Carvo and Mandi Ross

What’s in a name? In the case of eDiscovery, it’s all about what you’re trying to accomplish.

Legal and eDiscovery professionals can’t seem to agree on the appropriate term to describe the process of analyzing your data early in a case. Some refer to it as “Early Case Assessment (ECA),” while others refer to it as “Early Data Assessment (EDA).” Both reflect great ways to save time, money, and burden. But the similarity in these terms make distinguishing the two quite confusing. Instead of trying to make sense of the seemingly nonsensical (like how you park in a driveway and drive on a parkway), let’s refine the names to logically describe the process.

Early Case Assessment is Really Early Case Strategy (ECS)

The Sedona Conference Glossary, eDiscovery & Digital Information Management, Fifth Edition (available for download here) defines ECA as “The process of assessing the merits of a case early in the litigation lifecycle to determine its viability. The process may or may not include the collection, analysis, and review of data.”

That’s considerably different from EDA, which is defined as “The process of separating possibly relevant electronically stored information from nonrelevant electronically stored information using both computer techniques, such as date filtering or advanced analytics, and human-assisted logical determinations at the beginning of a case. This process may be used to reduce the volume of data collected for processing and review.”

Despite a clear difference between ECA and EDA, people still confuse the two. While ECA does involve assessment, it’s really about case strategy. It involves the considerations about the case – including liability analysis, damage assessment, adversary investigation, and litigation budget forecasting – that must be contemplated to determine the overall strategy for the case. Should you proceed to litigate the case? Should you consider phased discovery? Should you limit custodians? Should you settle? Should you push for dismissal? This is case strategy and should be completed early in a matter.

Since this is really a strategic process, why not change the name of it to Early Case Strategy (ECS)? Referring to those decisions as “ECS” instead of “ECA” would help eliminate the current ECA versus EDA confusion. Making early case strategy decisions depends on the needs of the case as outlined in Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Rule 26(b)(1) which states:

Duty to Disclose, General Provisions Governing Discovery; Discovery Scope and Limits; Scope in General

Unless otherwise limited by court order, the scope of discovery is as follows: Parties may obtain discovery regarding any nonprivileged matter that is relevant to any party’s claim or defense and proportional to the needs of the case, considering:

- the importance of the issues at stake in the action;

- the amount in controversy;

- the parties’ relative access to relevant information;

- the parties’ resources;

- the importance of the discovery in resolving the issues; and

- whether the burden or expense of the proposed discovery outweighs its likely benefit. Information within this scope of discovery need not be admissible in evidence to be discoverable.

The six proportionality factors of Rule 26(b)(1) significantly impact the strategy for the case and its viability in terms of deciding whether to proceed or settle.

ECS Legal and Practical Considerations

Making early case strategy decisions involves legal considerations that focus on several of the proportionality factors of Rule 26(b)(1). Those legal considerations include:

- Fact pattern evaluation: The facts of the case are essential to determining case strategy. The fact pattern associated with the case and “the importance of the issues at stake” is vital in determining the strategy for the case itself. Cases which involve reputational considerations may be more important to litigate than other cases, regardless of the amount at stake and the cost for litigation and discovery.

- Discovery scope assessment: Aside from the importance of the issues, the actual scope of discovery versus the amount in controversy can often decide whether to proceed with the case or pursue a settlement with opposing counsel. Considerations for evaluating discovery scope include:

- Custodians: The number of custodians potentially involved in the case can impact discovery scope considerably. Cases with many potential custodians drive up discovery costs, though not all potential custodians will be included in discovery. It’s important to assess how likely they are to possess unique relevant ESI as part of the discovery scope evaluation.

- Data sources: Just as not all custodians should be treated equal, neither should all data sources. Some data sources (g., email and office files stored locally or in the cloud) are easier to preserve, collect, and process than other data sources (e.g., data from mobile devices). The burden of discovery from each of the potential data sources must also be considered, as should any relevant internal IT and retention policies.

- Budget Projections versus Amount in Controversy: Prioritizing and ranking custodians based on their relevance to the case and the difficulty in discovering their data is key in estimating a budget that can be compared to the amount in controversy.

Understanding the facts of the case and the scope of discovery compared to the amount in controversy enables you and your team to make informed decisions as to whether to proceed or settle. These decisions, in turn, influence the preservation strategy associated with the case.

What Sedona Principle 6 Really Expects

Another valuable Sedona Conference resource for eDiscovery best practices is The Sedona Principles, Third Edition: Best Practices, Recommendations & Principles for Addressing Electronic Document Production (available here), which provides 14 principles that all professionals working in eDiscovery should know.

Perhaps the best-known principle is Principle 6, which states:

“Responding parties are best situated to evaluate the procedures, methodologies, and technologies appropriate for preserving and producing their own electronically stored information.”

New York Magistrate Judge Andrew J. Peck (now retired) famously cited Sedona Principle 6 in Hyles v. New York City, when – despite the fact that he was a proponent for the use of technology assisted review (TAR) and was the first judge to approve its use in a case – he ruled that the plaintiff couldn’t force the defendant to use TAR in that case in part because of Sedona Principle 6.

While that principle seems to imply that responding parties can do whatever they want when it comes to production, the responding party is still obligated to conduct discovery in a manner that is defensible. Part of early case strategy is to evaluate and determine the appropriate procedures, methodologies, and technologies for the case that are defensible, if the need arises.

Sedona Principle 6 also has five comments associated with it – 6.a through 6.e – that further set expectations associated with the obligation to conduct a defensible process. Notably, comment 6.c discusses “Documentation and validation of discovery processes,” with the idea that “Such documentation may include a description of what is being preserved; the processes and validation procedures employed to preserve, collect, and prepare the materials for production; and the steps taken to ensure the integrity of the information throughout the process.”

Parties don’t have to provide documentation about their processes – discovery about discovery – as a matter of course, but they need to be prepared to be able to use documentation to defend those processes if discovery deficiencies are shown. That’s an obligation that goes along with the freedom to evaluate appropriate processes in Sedona Principle 6.

Discovery is complicated and multi-faceted, and evaluating appropriate processes in Sedona Principle 6 requires the expertise to conduct that evaluation. That’s why Principle 6 also includes comment 6.e, which discusses the “Use and role of discovery counsel, consultants, and vendors.” As the comment notes: “Due to the complexity of electronic discovery, many organizations rely on discovery counsel, consultants, and vendors to provide a variety of services, including discovery planning, data collection, specialized data processing, and forensic analysis.” It’s important to “carefully consider the experience and expertise of potential consultants or vendors before their selection”, but the use of consultants and vendors can help ensure that your processes are defensible.

Why Identification is the Most Underrated EDRM Phase

When it comes to the stages of the EDRM life cycle, there are plenty of technology choices to support most of the phases except for the Identification stage. There are numerous eDiscovery review platforms available to support Processing, Review, Analysis and Production. There are also several platforms to manage and execute legal hold for Preservation, and many enterprise platforms today even support legal hold in place. And there are several platforms that support Collection of the many types of ESI that organizations manage today, including newer forms from mobile devices and collaboration applications.

The same is not true regarding the Identification stage, yet Identification is where the discovery process begins, and this presents a golden opportunity for cost-savings. The ability to accurately identify ESI that may be potentially responsive to the case is key to being able to determine your early case strategy. The identification stage is an opportunity for the legal team to target and organize both their custodians and data sources based on their relevance and burden. Index in place technologies today support the ability to search and analyze data, including file shares, workstations, and email, before incurring any collection or processing costs. This early analysis helps the legal team understand the fact pattern and the story the data tells. It enables reduction of the potentially responsive population before applying processes associated with the other EDRM phases, drastically reducing downstream costs. Effective early case strategy is based on fact finding and information, not speculation.

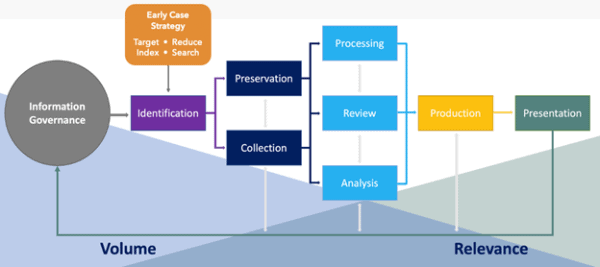

As indicated by the diagram below, this process of Target-Index-Reduce-Search during the Identification phase not only results in a more efficient discovery process, but it also supports making early case strategy decisions.

The early case strategy process is also supported by a simple, yet comprehensive, three-step workflow to help establish an accurate estimate for making those decisions which correlates with the mandates in Rule 26(b)(1). It begins with a quick relevancy assessment interview to score and rank each of the custodians based on their relevancy to the claims and defenses. Next, you evaluate the data sources associated with potentially responsive custodians based on the burden and effort to collect each of those sources – while also eliminating non-relevant and duplicative data sources. Finally, you scope the effort by preparing cost estimations to move the data from collection through review and production.

Having this information early allows the important process of ECS to really take shape. With critical custodian and data source information and corresponding eDiscovery cost estimates readily available, legal teams can create comprehensive discovery plans and scenarios to support negotiations and court proceedings; plans that have metrics to support them. Being armed with this information in negotiations and court proceedings is critical to success. These metrics are used to inform and articulate relevancy and burden, lending weight to any 26(b)(1) proportionality argument. It is important to think strategically from the outset to drive proactive rather than reactive decision-making.

Therefore, Identification is the most underrated EDRM phase, not only to ensure an efficient and effective discovery process, but also to make key strategy decisions as early in the case as possible.

How a Sound Early Case Strategy Approach Supports the Rest of the Case

All these considerations support what has been traditionally considered to be “early case assessment.” But this process isn’t really an assessment process; it’s a strategy process to make informed decisions about how to conduct the case.

Early case strategy involves evaluating the fact pattern and discovery scope to make informed decisions, considering the proportionality factors of Rule 26(b)(1) and Sedona Principle 6’s obligation to conduct discovery in a manner that is reasonable and defensible. These decisions set the foundation for other aspects of your case strategy including discovery scoping and budgeting, meet and confer preparation and negotiation, and development of an ESI protocol, which sets the stage for the rest of the EDRM life cycle.

Using the term “Early Case Strategy” would help resolve much of the current confusion around the conflation between ECA and EDA and is a more accurate reflection of what is really happening in what we have historically called “Early Case Assessment.” Let’s call it what it really is – Early Case Strategy (ECS)!

Authors:

Scott Carvo is a Partner at Warner Norcross + Judd LLP. Technically savvy with a background in information technology, Scott co-chairs the firms’ Data Analytics and eDiscovery Practice Group where he helps clients save money on discovery while delivering exceptional results. Scott is also an experienced litigator in matters involving non-competes, non-solicits, confidentiality agreements and general commercial litigation.

Mandi Ross is the CEO and Managing Director of Insight Optix, the company which developed Evidence Optix®, a powerful eDiscovery scoping, proportionality, and data source tracking technology.